Migration Policies played a central role in 13th elections, especially for collecting electoral consensus. The far right xenophobic wing built a campaign based on Merkel’s depiction as a “mother” always ready to welcome refugees, a “mother” who opens the borders. This behaviour, backed by the media, provoked major internal cultural-ethnic conflicts, exemplified in the wave of opportunism and hate generated by the Cologne’ episode. In spite of September initial governmental openings about Dublin agreement and borders control, followed by the rolling statements given by the German ministries on the possibility to receive more than 400 thousands refugees in the next few years, a grounded refugee reception policy has never been conducted. Only a few months later, Germany has started “filtering” refugees arrivals and fold to the nationalist decisions taken by Sweden, Denmark and Austria, thus differencing migrants on the basis of their origin (only Syrians), in addition, referring to the International Affairs, Germany started to endorse agreement definitely counter-productive for the refugees. As showed by 18th of March agreements between Turkey and EU. The new Merkel, energetically active in re-defining borders and limits of the European citizenship , has never been seen before, notwithstanding the efforts of the far right party to attach her this portrayal and consequently discredit the main political rival, Cdu. At the core of the contention, the public debate has betrayed the real issue about welcoming refugees, especially because CDU tried to answers to far right wing threats, also at a local level, containing refugees access and asylum attainment. The spirit and the numbers felt and declared initially in September could inaugurate an era of Wilkommenspolitik, but have rapidly vanished.

What happnened the thirteenth of March

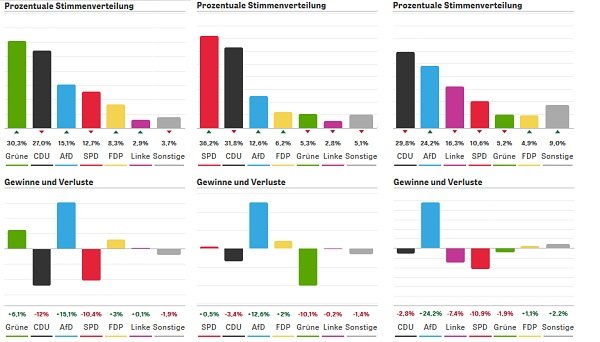

Regional elections held the thirteenth of March in Baden-Württemberg, Rheinland-Pfalz (Rhineland-Palatinate) and Sachsen-Anhalt (Saxony-Anhalt) saw the upsurge of AfD in all the three states.

The party, below the five percent in 2013 federal elections, won 15% of the vote in Baden-Württemberg corresponding to 23 seats on 143, 12.5% in Rhineland-Palatinate gaining 14 on 101 seats and more than 24% in the East German state of Saxony-Anhalt where took 24 on 87 seats. The quickest rise of a party since the end of the Second World War.

Merkel’s party, Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (Christian Democratic Union of Germany), has considerably lost support in all the three regions, respectively 12% in Baden-Württemberg, 3% in Rheinland-Palatine and 3% in Sachsen-Anhalt.

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (Alliance ‘90/The Greens) won in Baden Wurttemberg with the 30% of the votes, managing to get a region that has been held by the center-wing party since 1953. Similarly, the Greens lost 10% in Rheinland-Palatine and 1,9% in Saxony-Anhalt.

The left wing party, considering both the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany) and the De Linke (The Left), has paid off the elections with a slightly negative trend. The Social Democratic Party kept on stably in Rheinland-Palatine where they have been ruling since 1994, losing minimal electoral support in the other two regions. The Left has remained in a marginal position in both Baden-Württemberg and Rheinland-Palatine but lost his Saxonian overwhelming support (-7,4%).

“Party-ography“

Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany) has been founded in 2012 by Alexander Gauland a former State Secretary in Hesse, Bernd Lucke, an economist and Konrad Adam, a former editor and chief of Die Welt. The party first received support as a euro- sceptical, anti-Europe’s party, being helped by a team of economists and media backing.

In July 2015, Frauke Petry was elected as party’s main speaker, the hefty shift to the right pushed Lucke and other seven member of the previous establishment to resign from the AfD, saying that The Alternative was shifting “To a Pegida Party”. Afterwards, they founded a new party: ALFA - Allianz für Fortschritt und Aufbruch (Alliance for Progress and Renewal).

In the last year, the AfD`s program and its allies changed radically.

The Alternative presented itself as a euro-sceptic party, but after Petry’s election the program shifted towards anti-immigration, Christian-traditional family support, scepticism of Climate Change and active opposition to Germany’s energy transition.

F.E. Beatrix von Storch appealed against same-sex marriage and what she calls the “sexualisation of society”. Björn Höcke, leader of the party in Thuringia and Pegida sympathizer, has become famous for his statement about “the African way of reproducing” and more xenophobic statements.

The party hardly exploited the Refugee Crisis and New Years’ Eve facts in Cologne to make populistic propaganda against Merkel’s immigrant policy, reaching the peak when at the end of January a party member invoked the police to be given powers to use firearms against illegal migrants. The statement was re-asserted by the spokesman Frauke Petry during an interview the 30th of January.

At the moment the party seems to collect the friendship of the right wing liberal populist party Die Freiheit (The Freedom) and the encouragement of the Anti-Islamic/far right popular movement Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West), known as Pegida.

In a poll conducted by the AfD among its members, 94,7 % stated that they would like to abolish the seek asylum right, which is anchored in the German constitution. In this regard, the AfD members are more reactionist than the the NPD, the German Neo-Nazi party, in Rheinland-Palatine, which admits asylum concession for a short period of time.

At the party’s main public assembly, newspapers of the former were distributed and members of the latter were sitting in the first lines.

How to read the results

The elections clearly displayed the rise of the far right in Germany. However, 80 % percent of the voters decided for parties that either support Merkel’s call for a European approach to the refuge crisis and against immigration quotas or demand immigration policies that are more liberal.

Some commentators read the results as an act of protest against the established parties and Merkel’s immigration policy. This implies that the votes for the AfD should, first of all, be read in the context of the refugee crisis and not as an appraisal of the whole AfD party programme. One has to see how the party will perform when their main topic, the refugee crisis, is not dominating the headlines anymore.

Nonetheless, there will remain a part of the German population – often described as the losers of modernisation – that cannot identify themselves with the established German parties. It must be the task of these parties to convince supporters of the AfD that nationalism cannot be an answer to the problems of our times and that the seemingly easy answers of populist movements will never solve the complex problems that we are facing. What the established parties should not do, is to please voters of the AfD by revising their stance on immigration policy to a more restrictive and inhuman position.

What expect from the future

On a regional perspective, the electoral results have been interpreted by political columnists in radical different ways.

Saxony-Anhalt has always been a right-centered region, where population and some of CDU members did not tolerate Merkel`s decision to re-affirm her immigration policy, in spite of the pre-election polls showing decreasing backing. In Saxony-Anhalt CDU votes went directly from her party to the far right AfD, so as the all the political balance deviated to the right.

In the other two regions, it is more difficult to interpretate this kind of data. Merkel coherence apparently did not influenced the vote, since AfD took seats uniformly from Greens, SPD and CDU. Moreover, the two candidates who backed this kind of policy, respectively Malu Dryer in Rheinland-Palatine and Winfried Kretschmann in Baden-Württemberg, won.

Another approach to explain the rise of the AfD is the mobilisation of non-voters, especially the so-called “worried citizens”. These citizens belong to the middle class and would normally not been attracted by a xenophobic rhetoric, “I am not a racist, but …”, however, decided to vote for AfD because of safety issues. This class of citizens made the difference between the voter turnout of around 64 % in the last elections in 2011 and the turnout of around 71% in the recent elections. They represent the type of citizens that has the potential to significantly influence election outcomes in each European country.

On the national perspective, AfD achievements must not be underrated. The party can easily exploit the longstanding presence of the eleven year on charge tired Chancellor Merkel, whose party in the eyes of the electors seems to care much more about Europe’s “future” and “integrity” (not to say inference) than the national economy and safety-issues.

Therefore, it is important to read these regional elections as the spectrum of 2017 elections, where Angela Merkel will not re-candidate and her main rival, Julia Klöckner, lost in Rheinland-Palatine against SPD.

Before 13th of March, Germany seemed to be immune to the materializing rise of extreme-right wing populist parties. To believe in this moment that Germany is dealing with a fleeting phenomena is almost impossible and necessitates a reflection about the future of moderate parties and ideas, not just in Europe.

Other issues that require attention are media backing of these nationalist forces and the lack of an active grassroots counter-narrative from the moderates.